Horn-a-Tron

Some of the publicity put out for the show has perhaps been unintentionally slightly misleading! I did have a dream of having a French horn section in the show, but that dream has been realised through… technical means :)

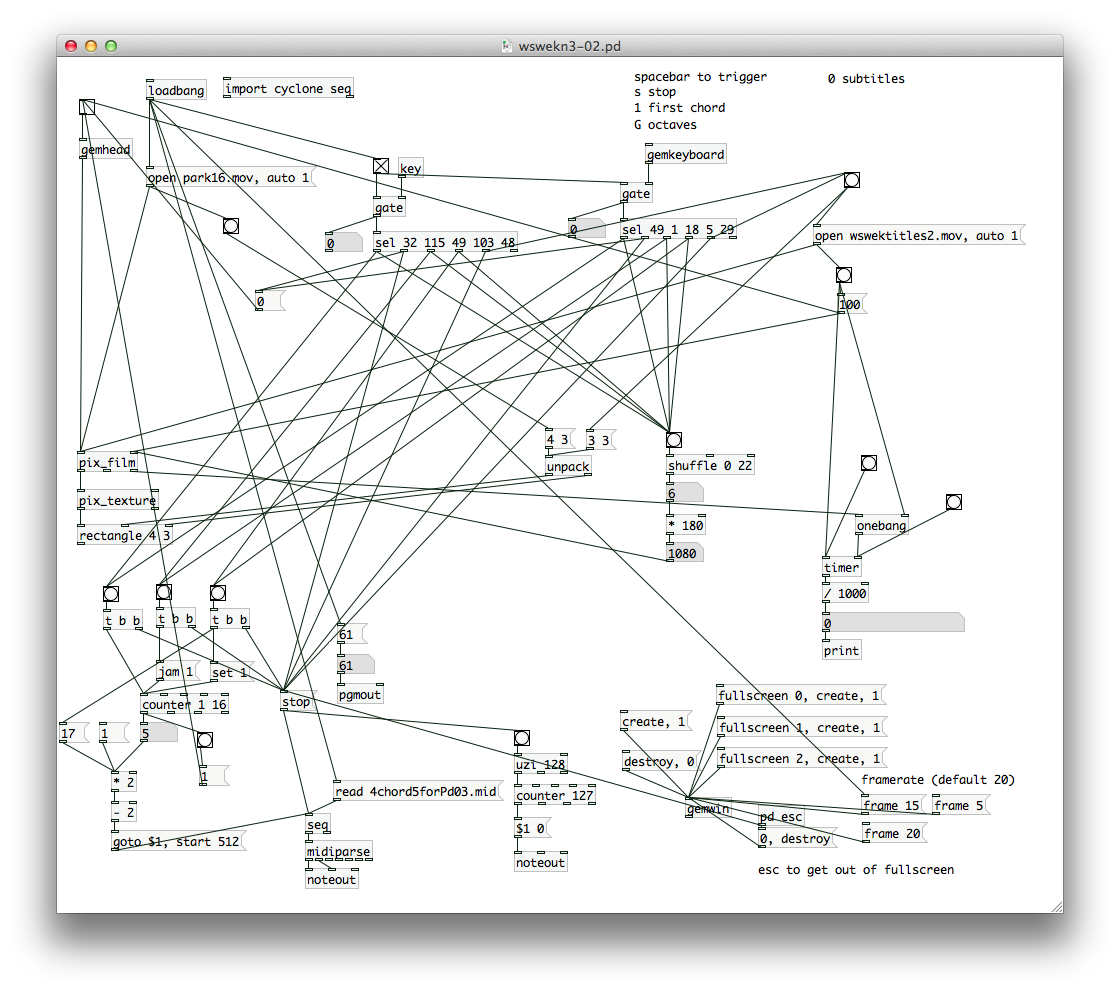

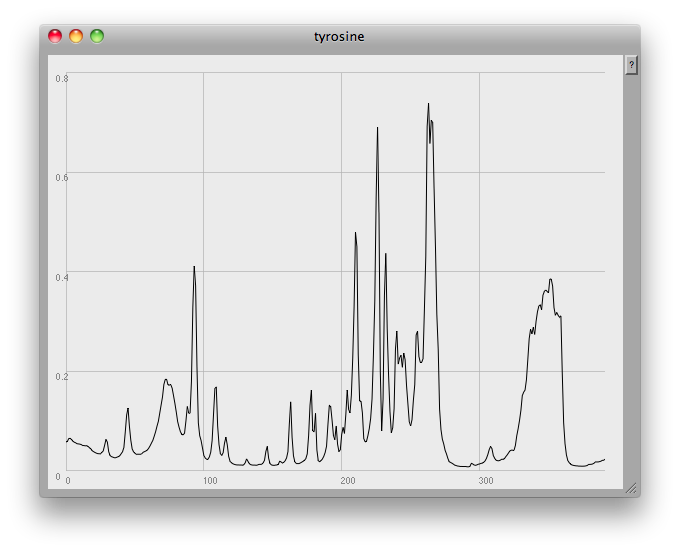

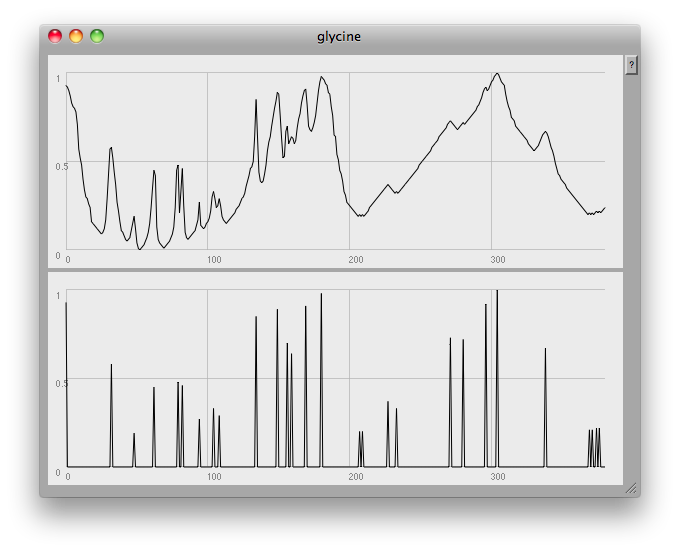

Instead of live players, I've invented the 'Horn-a-Tron'. This is a Pd patch which plays back midi horn sounds alongside video clips of sixteen horn players – with thanks to Steve Park for the horn vids. I'm not going to put up a clip of this working just yet, spoil the effect. But here's the patch: